This original reporting and analysis, sixth in a series interpreting the results of Iowa’s 2024 state and federal elections, first appeared at Bleeding Heartland and is shared here as part of the Iowa Writers Collaborative. For regular emails linking to all recent Bleeding Heartland articles and commentary, subscribe to the free Evening Heartland newsletter. If your email provider truncates this post, you can read the whole article without interruption at this link.

The 2024 elections could hardly have gone worse for Iowa Democrats. Donald Trump carried the state by more than 13 points—a larger margin than Ronald Reagan managed here in either of his campaigns, and the largest winning margin for any presidential candidate in Iowa since Richard Nixon in 1972. The GOP swept the Congressional races for the second straight cycle and expanded their lopsided majorities in the legislature.

Support for Democrats has eroded in Iowa communities of all sizes—from large metro areas like Scott County (which voted for a Republican presidential candidate for the first time since 1984) to rural counties that were always red, but now routinely deliver more than 70 percent of the vote to GOP candidates.

This post highlights the growing problem for Democrats in Iowa’s mid-sized cities. I focus on eleven counties where Democratic candidates performed well in the recent past, but now trail Republicans in state and federal races.

Changing political trends in mid-sized cities explain why Democrats will have smaller contingents in the Iowa House and Senate than at any time since 1970. Voters in six of these counties also saved U.S. Representative Mariannette Miller-Meeks from a strong challenge by Democrat Christina Bohannan in the first Congressional district.

COUNTIES WITH MID-SIZED CITIES WHERE DEMOCRATS USED TO WIN

The eleven counties are listed here in descending order by population, with mid-sized cities in parentheses. Among Iowa’s 99 counties, Warren ranks eleventh in population, and Boone is number 23.

Warren (Indianola)

Clinton (Clinton)

Cerro Gordo (Mason City)

Muscatine (Muscatine)

Marshall (Marshalltown)

Des Moines (Burlington)

Jasper (Newton)

Webster (Fort Dodge)

Wapello (Ottumwa)

Lee (Keokuk and Fort Madison)

Boone (Boone)

I selected these counties because of several common features. Most are anchored by cities with between 10,000 and 30,000 residents. (A few of the cities have populations slightly below 10,000.) All of the mid-sized cities are “nonmetropolitan regional trade centers,” where many Iowans living in smaller communities work, shop, or receive services such as health care. Aside from Warren County, which is part of the Des Moines metro area, all are part of what economists call “micropolitan statistical areas.”

Ten of the eleven are among Iowa’s 31 “pivot counties,” which voted for Barack Obama in 2008 and 2012 but for Trump in 2016 and 2020. Warren County voted for Obama in 2008 but for Mitt Romney in 2012 before decisively favoring Trump.

Another shared bit of history: residents of these counties used to send Democrats to the statehouse. The last time Democrats controlled both state legislative chambers (from 2007 through 2010), the party held the Iowa House seat in Boone and the House and Senate seats in Muscatine, Marshalltown, Burlington, Keokuk, Fort Madison, Clinton, Mason City, Indianola, Newton, Ottumwa, and Fort Dodge.

NO LONGER COMPETITIVE AT THE TOP OF THE TICKET

Back when Iowa was a swing state in presidential elections, Democratic nominees often won counties containing mid-sized cities. Al Gore carried eight of the eleven discussed here when he edged out George W. Bush by 0.3 percent in 2000. Even in 2004, when John Kerry lost statewide by less than a 1-point margin, he received more votes than Bush in Cerro Gordo, Clinton, Muscatine, Des Moines, Jasper, Webster, Wapello, Lee, and Boone counties, and trailed by only about 100 votes in Marshall County.

As mentioned above, all of these micropolitan counties flipped from Obama to Trump. Most weren’t even close in the last two presidential elections. I compared the certified county-level vote totals and percentages for 2020 with unofficial results from the Iowa Secretary of State’s office for the latest election. You can find all of my calculations here.

Between 2020 and 2024, Trump increased his share of the vote and his raw vote advantage over the Democratic nominee in all eleven counties. In most of them, he also received more total votes this year than in 2020, even though Iowa’s turnout was slightly lower.

Whereas Trump defeated Joe Biden by single-digit margins in five of the counties (Clinton, Cerro Gordo, Muscatine, Marshall, and Des Moines), he won all eleven by double digits this year, and outpolled Kamala Harris in most of them by more than 15 points.

Across these eleven counties, Trump netted a 31,794-vote advantage over Biden, but led Harris by 45,567 votes.

Iowa’s U.S. Senate elections have followed a similar trend. Democratic icon Tom Harkin routinely won all eleven of these counties—even in his closest re-election bid in 1996. But in 2014, when the Senate seat was open due to Harkin’s retirement, Democratic nominee Bruce Braley only carried four of them (Cerro Gordo, Clinton, Des Moines, and Lee). Democratic challenger Theresa Greenfield won only one of them in 2020, and her margin over Joni Ernst in Cerro Gordo was just 195 votes.

Also worth noting: all eleven of these counties voted for Democrats Tom Vilsack and Chet Culver when they were elected governor in 1998, 2002, and 2006. But the last time Iowa had a close gubernatorial election in 2018, Democratic nominee Fred Hubbell lost eight of these counties. While he did outpoll Kim Reynolds in Clinton, Des Moines, and Lee counties, Hubbell carried all of those by much smaller margins than Democrats had in governor’s races they won.

INCREASINGLY FAVORING REPUBLICANS FOR CONGRESS

For many years, Democrats running for Congress could count on support from many of Iowa’s mid-sized cities. Christie Vilsack carried Boone, Webster, and Cerro Gordo counties in 2012, when she lost to Republican incumbent Steve King in Iowa’s fourth district. In 2014—a very good year for Republicans—Democratic incumbent Dave Loebsack carried Clinton, Lee, Des Moines, Wapello, and Jasper counties en route to beating GOP challenger Mariannette Miller-Meeks in what was then the second district. Miller-Meeks won Muscatine County that year by a small margin.

Things had changed dramatically by 2020, when Miller-Meeks defeated Rita Hart by the infamous six votes in IA-02. Hart won her home county of Clinton by 2,052 votes, but fell short in the other counties with mid-sized cities. Miller-Meeks had vote margins of 2,627 in Wapello County (her home base), 3,082 in Jasper County, 2,176 in Lee County, 548 in Muscatine County, and 373 in Des Moines County.

When you lose by six votes, anything could be a decisive factor—even the ballot layout in deep-blue Johnson County. But clearly Miller-Meeks would not have won without riding Trump’s coattails in formerly Democratic working-class towns.

This year’s race in southeast Iowa’s U.S. House district, now numbered IA-01, illustrates how much Republicans benefit from a new political landscape in mid-sized cities.

Bohannan’s campaign invested heavily in GOTV in Johnson County (the Iowa City area). The strategy produced record turnout and a huge margin for the Democrat of more than 35,000 votes. Bohannan also carried Scott County, the largest by population in the district.

But even though Miller-Meeks underperformed Trump across the board, and Wapello now lies outside her district, the Republican did well enough in the other counties to come out on top by 0.2 percent in a district Trump won by 8.4 percent.

IA-01 hasn’t been called yet, because Bohannan has asked for a recount in all 20 counties. But it will be virtually impossible for her to overcome an 801-vote deficit.

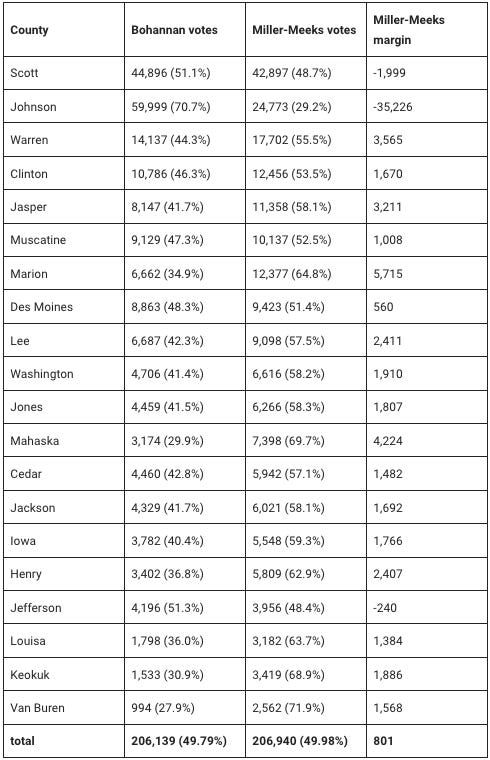

I made this table using the results on the Iowa Secretary of State’s website, which were updated following county canvasses on November 12 and 13. Counties are listed in descending order by total votes cast in the Congressional race.

You could argue that almost any of the red counties won it for Miller-Meeks, since they provided a margin greater than 801 votes.

But it’s one thing for Bohannan to get blown out in traditionally red counties like Mahaska (Oskaloosa area) or Marion (Pella and Knoxville). It’s another to lose badly in counties Democrats were winning within the past decade, like Jasper, Lee, and Clinton counties.

The realignment in mid-sized cities began before the Trump era, as shown by Ernst’s performance in the 2014 Senate race. But in that election, Braley still managed to carry Clinton, Lee, and Des Moines counties while losing statewide by 8.3 points. If Bohannan could have kept it a bit closer in mid-sized cities, she would be headed to Congress.

FROM MOSTLY BLUE TO ALL RED IN STATEHOUSE RACES

The erosion of Democratic support in micropolitan areas has been most devastating for the party in legislative elections. Even after the 2010 Republican landslide—when the GOP posted net gains of sixteen Iowa House seats and six Senate seats—Democrats still represented most of the mid-sized cities in at least one chamber. Those areas had been electing Democratic lawmakers for decades.

When the legislature reconvenes in January 2025, not one Democrat will represent any of these communities. Here’s how the disaster unfolded in the various cities.

Indianola: Republicans won the state Senate seat by defeating a Democratic incumbent in 2010. The GOP also won the area’s House seat in 2008, lost it in 2012, and won it back by defeating an incumbent in 2020.

Clinton: Republicans picked up an open Senate seat in 2018, when then-Senator Rita Hart became the Democratic nominee for lieutenant governor. The GOP picked up the House seat in 2022 when a long-serving Democrat retired.

Mason City: The redistricting plan adopted in 2021 put two incumbents in the same GOP-leaning Senate district. The Democrat retired, allowing the GOP senator to hold over in 2022. Republicans held the Senate seat in 2024 and picked up the open House seat, when a long-serving Democrat retired.

Muscatine: Republicans defeated Democratic incumbents in the House in 2010 and in the Senate in 2016.

Marshalltown: Republicans defeated Democratic incumbents in the Senate in 2016 and in the House in 2024.

Burlington: Republicans defeated Democratic incumbents in the Senate in 2016 and in the House in 2022.

Newton: Republicans picked up an open Senate seat in 2018 and an open House seat in a 2021 special election.

Fort Dodge: Republicans defeated a Democratic senator in 2014 and picked up the House seat in 2018, when a long-serving Democrat retired.

Ottumwa: In what initially looked like a fluke, but in retrospect was the canary in the coal mine, a Republican defeated a Democratic senator in 2010 by ten votes. The GOP has held that Senate seat by increasingly large margins and defeated a long-serving House Democrat in 2020.

Keokuk and Fort Madison: Republicans picked up the House and Senate seats by defeating Democratic incumbents in 2020.

Boone: Republicans have long held the area’s Senate seat and have represented the city in the House since defeating a Democratic incumbent in 2010.

When Democrats were down in the Iowa House by 60 seats to 40 after the 2010 red wave, I thought the party was at a low point. Now that the Republican majority has grown to 67-33, it’s hard to see a path back to 40 House seats for Democrats.

This year, the party did not even field candidates for the House or Senate districts containing Fort Dodge, or for the House seat covering Keokuk and Fort Madison.

Democrats had candidates competing for the House seats in Boone, Indianola, Ottumwa, Newton, and Muscatine, but the Iowa Democratic Party spent little or no money on those races. The same goes for the Senate races in districts that include Muscatine, Boone, Marshalltown, and Mason City.

Democrats spent minimal amounts to support their state House candidates in the Clinton and Burlington area districts. Republicans spent more than ten times as much on those races.

The GOP spent more than $400,000 to defend the Senate seat covering Lee County and the Burlington area of Des Moines County. The Iowa Democratic Party spent only about $56,000 on that race.

Democrats spent more than $100,000 trying to defend the open state House seat in Mason City, but Republicans spent more than triple that amount on the race.

Democrats spent nearly $400,000 trying to save State Representative Sue Cahill (an assistant minority leader) in the Marshalltown-based House district 52. But Republicans and their allies poured more than half a million dollars into that race.

Trump easily carried all of the the state legislative districts in Iowa’s micropolitan areas. Some of the Democratic candidates outperformed Kamala Harris, but not by nearly enough. For instance, Trump carried House district 38 (Newton area) by nearly 25 points: 61.4 percent to 36.8 percent. In the state House race, GOP incumbent Jon Dunwell defeated Democrat Brad Magg by a much less impressive margin of 55.7 percent to 44.2 percent. But losing by less than the top of the ticket doesn’t get Democrats any closer to a House majority.

NOT AN IOWA-SPECIFIC PROBLEM

One of the most common questions I hear is “What happened to Iowa?” Those familiar with our state’s political geography are bewildered that Democrats could be losing in places like Fort Dodge and Ottumwa and Burlington, which were strongholds for generations.

It’s tempting to blame Iowa Democratic leaders for flawed messaging or organizational failures. No doubt, the party and its candidates have room to improve.

But this trend is not unique to Iowa. Across the country, voters in predominantly white working-class areas have drifted toward the GOP over the last ten to fifteen years. Many ancestrally Democratic towns have sent Republicans to Congress or the state legislature, as traditionally conservative suburbs have begun to elect Democrats. Carlton County, Minnesota, located in that state’s “Iron Range,” just voted for a Republican for president for the first time since 1928. Carlton is demographically similar to many of Iowa’s micropolitan counties. It has just under 37,000 residents; about 89 percent are white, and around 25 percent who are at least 25 years old have a college degree.

There’s no consensus about why Republicans have been doing so much better among white voters who didn’t go to college. Harry Enten identified the phenomenon as a decisive factor in Iowa’s 2014 Senate race and noted at that time, “if that shift persists, it could have a big effect on the presidential race in 2016, altering the White House math by eliminating the Democratic edge in the electoral college.”

The decline of organized labor has likely played a role—but there’s no simple fix, since many of the rank and file union members who still live in these communities now support Trump and other Republicans.

I suspect conservative domination of the information space (through talk radio, television networks, popular websites, and social media) has been important. Media consumption habits are increasingly correlated with partisan preferences. And though correlation does not prove causation, right-wing media relentlessly push topics that play to Republicans’ strengths, like immigration or culture war issues. Even the best Democratic candidate would struggle to overcome negative stereotypes reinforced daily for years.

Whatever the reasons for the decline, Democrats need to find their footing in Iowa’s mid-sized cities in order to win back legislative, Congressional, or statewide offices.

Nice photo of the courthouse. I can just barely see the Messenger building too.

Excellent, detailed analysis, as always.